He'll whip the pants off the bad guys!

Friday, September 29, 2006

Friday with Freakazoid...'s supporting cast!

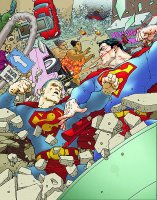

For those who may remember, Freakazoid started as a sort of anthology show, and Freakazoid wasn't the only one to take the spotlight. Today, we shine that bright white light on one of Freakazoid's finest allies, the Huntsman.

He'll whip the pants off the bad guys!

He'll whip the pants off the bad guys!

Wednesday, September 27, 2006

The things that bring you here

So, I shouldn't be surprised that a search for Organic Spider-Man comics turned up my blog, what with all my ranting and raving about web-shooters. The thought, however, of comics printed on untreated paper, using only natural dyes and no pesticides, tickled me mercilessly.

It looks like my mis-coined term "misandrony" is catching on, if a search for misandrony definition of is any indication.

To my good friend in Winnipeg who asked what does it mean when a grown man throws a tantrum, I answer that it clearly means you're reading a post by James Meeley.

Then, there's searches like Nasty Linda and Vicky wedgie, where I'd prefer not to know.

The Fortress of Soliloquy: your number two source for Vicky wedgie on the web. I swear, some days it's like I'm the butt of some cosmic joke.

It looks like my mis-coined term "misandrony" is catching on, if a search for misandrony definition of is any indication.

To my good friend in Winnipeg who asked what does it mean when a grown man throws a tantrum, I answer that it clearly means you're reading a post by James Meeley.

Then, there's searches like Nasty Linda and Vicky wedgie, where I'd prefer not to know.

The Fortress of Soliloquy: your number two source for Vicky wedgie on the web. I swear, some days it's like I'm the butt of some cosmic joke.

Tuesday, September 26, 2006

Marvel Comics I'd Write for Free: Civil War

Civil War, in case you haven't heard, is Marvel's latest attempt to parallel events in the real world. Unfortunately, it seems that they their job too well, and entered into a Civil War without an exit strategy.

All throughout the lead-up and duration of this series, Marvel's higher-ups have said that they're not endorsing either side, that neither group is "right." Meanwhile, Tony Stark's behind-the-scenes manipulation of longtime friends and colleagues, the pro-Registration side's willingness to play Odin and dance with devils, and Captain America's mere presence on the anti-Registration side, have told a very different story, a tale of clearly-defined good and evil, and no amount of panels where Tony Stark wonders about his choices or where Cap looks like a fanatic, will change that.

Then, there's all the smaller problems. Why are all the intellectuals on the pro-Registration side? Why are Tony Stark, Peter Parker, and Reed Richards acting so wildly out of character? And the one that's bugged me ever since I read Illuminati: how the hell can you justify the Stamford incident?

The new New Warriors may be a relatively inexperienced team, they may be in it more for the fame and money than they should, but of the four members I see on that team, three of them (Namorita, Night Thrasher, and Speedball) have been with the team since its inception, and have battled cosmic-level threats to the world. They routinely battled with the Sphinx (who at one point gained the ability to warp reality, as I recall), former Galactus herald Terrax the Tamer, and other fairly major villains. They've earned the right to some respect. Nitro, on the other hand, is something of a D-list villain, a character I hadn't even heard of until I picked up the Essential Official Guide to the Marvel Universe, whose power is "exploding" and whose only claim to fame is being involved in the death of Captain Marvel. This isn't a Year-One Power Pack going up against Dr. Doom, this is a group of fairly experienced heroes going after a lame villain. How is it that they were so "out of their league"? How is it that they could be blamed for the incident, that they "should have known better," and called the Avengers or some such nonsense? Last I checked, there wasn't a superhero phone tree. Is Spider-Man supposed to stop and call up the X-Men when Juggernaut starts rampaging through Times Square? How exactly does the hierarchy proceed? If Galactus shows up, do you call the Fantastic Four or the Avengers? I mean, the Avengers have more firepower, but the FF's got the experience. The idea that the New Warriors should have stepped back and called for help, that they were out of their league fighting freakin' Nitro, is beyond absurd.

No, Civil War started on the wrong foot and simply hasn't recovered. Here's how it should have gone.

First off, the Illuminati was a dumb idea which should have never been. It's elitist, it's vaguely racist, and it's another one of those "a dark secret from the earliest days of [insert character]'s history comes to light" plots that has been used, reused, and overused since Identity Crisis (see also: Gwen Stacy, Barry Allen, Professor Xavier, Thomas Wayne, etc.). Besides that, a major crisis, almost infinite in its scope, results from the dissolution of the relationship between the universe's primary heroes...seems to me that it's been done before.

The difference, of course, is that DC exploited a relationship that already existed, they didn't do a "JLA: Trinity" one-shot to set it up first.

What we do instead is a one-shot or brief miniseries (no more than 3 issues) about the new wave of "superhuman chic" sweeping the nation. Shows like the New Warriors and X-Statix have become increasingly popular, and every network wants to cash in. Meanwhile, the Masochist Marauders (from Spectacular Spider-Man #21--teens who fake muggings in order to get beaten up by superheroes) are a Jackass-style Internet sensation, and copycats have sprung up all over the country. Deaths due to radiation poisoning and other attempts to re-enact superhero fights and origins have been steadily rising. Rising up the bestseller charts is "The Capedemic: How So-Called Superheroes Endanger us All," a book which proposes the idea that the number of averted disasters and saved lives simply doesn't make up for the danger inherent in superheroes' existence. Finally, premiering this season on Fox: "Big Shoulders," a reality show about a new team of teenage superheroes operating in Chicago, the 'Chicago 7.'

Next, one tragedy isn't going to set the wheels in motion. There ought to be a series of events, and the first involves the Hulk. Things can go down pretty much the way they happened in Illuminati--Hulk rampages through a small midwestern town, completely unstoppable for the several minutes before heroes and Hulkbuster Units can arrive to bring him down. Midwestern politicians come under pressure to stop the spread of metahuman-related violence. When it was primarily an issue for New York, it was a different story, but superhuman menaces have begun popping up with more frequency in California and in various states across the country. S.H.I.E.L.D. is pressured by Congress to do something about the Hulk, hoping to use that as a stop-gap procedure, taking attention away from the metahuman problem. They go to the Avengers, telling Iron Man "he was on your team, he's your responsibility." Tony brings together Captain America, Hank Pym, Wasp (the only original Avengers left), Doc Samson (who knows the Hulk best), and Reed Richards ('cause he's a smartie), along with a somewhat sedated Bruce Banner. Bruce understands the problem at hand and agrees that he's simply too dangerous to continue roaming around the country. Tony suggests placing him on an orbital platform--he has several satellites in various places around the solar system that could be easily and remotely modified. They settle on a research satellite orbiting Mars. Bruce will be provided with all the amenities of home, and the self-replicating nanotechnology will ensure that any damage done by the Hulk is strictly temporary. Meanwhile, a research team on Earth will step up their quest to cure his condition. They send Bruce up, but he never makes it to the satellite. It's not clear who or what caused the malfunction.

Barely a week goes by before the Abomination breaks out of prison and ends up in St. Louis. The first superheroes on the scene are the Chicago 7, three weeks into the new season. The event goes live, with producers hoping to turn it into a publicity stunt. It works: Abomination stomps the rookie heroes, and their inexperience only makes things worse. Hundreds die, the property damage is astronomical, and all in the fifteen minutes it took for a Quinjet and several S.H.I.E.L.D. hovercraft to arrive from the East Coast. Within days, a superhero registration bill is circulating around Congress.

Now, this is about where my two ideas for this story diverge. For this first one, I'll accept the basic premise that it's an ideological war between Captain America and Iron Man, except, you know, without the idiocy.

Captain America makes a public speech against the bill, and the act's supporters need a spokesperson from the costume crowd. They end up picking Iron Man, due to his prestige and sway with the superhero community. Tony is torn, and as much as he may agree with Captain America, he can't help but wonder if maybe the act would be a good thing. He reads through the text several times, he speaks with the drafters and S.H.I.E.L.D. executives about the logistics. Everything would remain more or less the same, really. The superheroes would register with S.H.I.E.L.D., who would provide them with training and license cards, similar to the Avengers Membership Cards. The registered heroes would have the option of becoming S.H.I.E.L.D. employees, which would allow them to do their usual superheroing and civilian living, as long as they took the occasional S.H.I.E.L.D. mission. For this, they would receive a stipend and benefits (health insurance and life insurance are a bitch for the capes-and-tights set). All this information would be kept absolutely secret, and only top S.H.I.E.L.D. brass would have access to it.

And those who refused to register? If apprehended, they would be offered the chance to register. If they continued to refuse, they may be charged a fine, and they might face some time in prison.

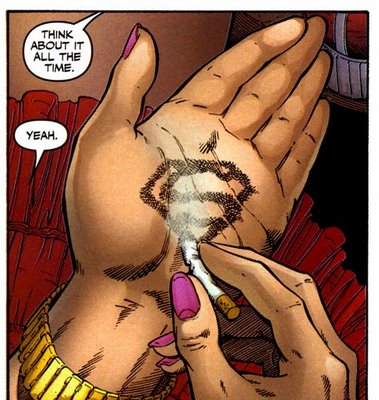

Tony turns to Peter Parker for moral guidance. Peter's feelings about S.H.I.E.L.D. are mixed, and he's never been on the best of terms with the general populace. He and Tony have a long conversation about the matter, with Peter mostly playing the anti-registration side. That is, until Tony wonders aloud how many innocent lives might be saved if young superhumans had the proper training. Peter thinks back, back, to how a little professional training might have allowed him to reach Gwen Stacy in time, or to catch her without killing her, how a that extra edge against Doctor Octopus might have let him save Captain Stacy, how if he had gone to S.H.I.E.L.D. instead of the TV station, he might have been around to stop that robber...

It becomes clear to Peter that superheroes have been given great power, and the registration act is merely asking them to accept the responsibilities that come with such power. He joins Tony in support of the Registration Act. Tony immediately sets out to get the best and brightest in the superhero community to figure out the logistics, to ensure that security, training, and enforcement all works out with the heroes' best interests in mind. Hank McCoy won't return his phone calls.

Meanwhile, the X-Men are placed in a difficult situation. Cyclops and Wolverine and their ilk see the Act for what it is: a broadened version of the Mutant Registration Acts that have circulated around Congress for years. Cyclops considers coming out in opposition, but fears that it may draw unnecessarily negative attention to the dwindling Mutant community. Supporting the Act, however, would be outright hypocrisy, and would go against everything Xavier ever stood for. Not wanting to make the school a fort against the United States government, he declares official neutrality on the subject. Wolverine is understandably upset by this and leaves the mansion in protest.

The Act passes, despite Captain America's public speeches in opposition. Things initially appear to be going well. The superhero-related shows that started much of this ruckus have been quietly cancelled, superheroes are registering voluntarily by the dozens, and the anti-registration heroes? Reed Richards registers, as do Sue and Ben, but Johnny Storm refuses and leaves the team. Sue is still unsure about the whole thing, and Ben just won't talk about it, but both recognize that their public identities and publicly-known headquarters make it difficult to make a stand against the Act. Reed just hopes to oversee the registration operations, to ensure that identities are actually kept secret from prying eyes, and that the superhero training goes well, that all this will ultimately help the superheroes' cause.

It starts with Night Thrasher (and why not? Rather than needlessly kill him off, let's give him a purpose), who is in the process of battling a minor supervillain (I dunno, someone like Nitro, I suppose), when a police officer tries to arrest him. NT tries to tell him that he doesn't have time for this, but the cop draws his gun and insists. Night Thrasher knocks him out, then does the same with Nitro, leaving the supervillain in handcuffs with a power inhibitor collar on. NT escapes, but now is wanted for assaulting a police officer in addition to refusal to register. The scene plays out across the country: Hercules has to shrug off bullets from both sides while he stops a Hydra terror plot in Times Square, Darkhawk finds himself on the wrong end of a SWAT team after stopping a school bus from going over a bridge in San Francisco, and finally, some trigger-happy security guard fires at Speedball during a bank robbery/hostage situation, and the ricochets from his kinetic field kill two innocent bystanders. The media picks up the story nationwide, using Speedball as the prime example of why heroes need to register, how dangerous the anti-registration heroes are, and why young people shouldn't be allowed to operate as superheroes. The atmosphere shifts; first police are recommended across the country to use riot teams to apprehend rogue superheroes, then S.H.I.E.L.D. teams are dispatched onto regular superhero patrols. Iron Man offers his services to help round up the unregistered heroes, in hopes that he can take control before they start using lethal force in these apprehensions. Things are clearly spiraling out of control.

Meanwhile, Captain America has become the hero of the anti-registration movement. He steps into this role naturally, finding them across the country and running a sort of underground railroad for anti-reg heroes. Things with Cap proceed pretty much the same as they have in the regular series, what with him assembling his Secret Avengers and continuing their superheroic duties in secret. The only difference is that some of the heroes, particularly some of the younger ones, are chafing under Cap's cautionary ways. They want to break out and really fight back, but Cap doesn't want to start an all-out war with the American government. These dissenting heroes--including Black Cat, Jack Power, Deathlok, and War Machine (assuming all of them are still alive)--begin sneaking out of the base and causing anti-government havoc. Cap tries to hold together his Secret Avengers, despite the growing schism, but more and more of his team are choosing proactive methods over reactive ones. Of course, those methods are being spun by the media and the government to increase the furor over the issue, and it's quickly nationwide martial law on unregistered superheroes.

Tony Stark decides that this needs to end quickly; he realizes that the situation has long been out of his control, and he assembles his team to set a trap for Cap's Secret Avengers, in hopes of stopping the madness before America becomes a superhuman police state. The battle goes poorly for both sides; two of the Young Avengers and Dazzler are captured, while Sue Storm defects to Cap's side.

Cap and Tony don't fight, not really. Tony explains his position, how he just wants to help, he wants to wrest control of the system back from the government, and he can't do it alone. Things are out of his hands, and the vaguely anarchist actions of the Secret Avengers are only making things worse. Cap tells Tony that he's not trying to take down the government, he's just trying to hold his team together, and it's breaking apart under the pressure. He's disappointed that Tony would stoop so low as to set a trap for them, and he doesn't want to fight, but he's not going to back down. The Registration Act is wrong, and if Tony can't see that with S.H.I.E.L.D. patrols hunting down superheroes in the streets, then there may be no hope at all. Cap tells Tony to call off his troops, that this can still end peacefully, but Iron Man morosely looks away and pulls his mask back down. "I'm sorry, Cap. I can't do that." He fires his repulsor-ray, but finds it deflected back at him by Captain America's mighty shield. Cap calls for a retreat, while Iron Man's enforcers press on. They teleport away, with help from the Invisible Woman, and return to their base.

Back in the hideout, licking their wounds, the Secret Avengers have a breakdown. Cloak is pissed, and he leads the proactive heroes out of the hideout. Captain America is watching his resistance fall apart, and he wonders how it got to this point. Maybe Tony's right, maybe it would be better if they sat down with the pro-Registration folks and hammered out a compromise. Around that time, a young and idealistic superhero by the name of Gravity awkwardly steps up to Captain America, clumsily salutes, and introduces himself, saying how much of a pleasure it is to meet him, and how it was his shining example, his steadfast adherence to the ideals that make this country so great, which inspired him to put on a mask and tights and fight the good fight. Captain America shakes the young man's hand, and is suddenly reassured that he's doing the right thing. He thanks the lad, and solicits volunteers to go after their black sheep.

The splinter Avengers, however, aren't doing so hot. Following a raging Cloak, they decide to raid the S.H.I.E.L.D. prison facility where their teammates are being held, in hopes of causing serious damage while they're at it. They successfully break into the prison, not realizing that both the captured heroes and various villains are temporarily being held in the facility. The ensuing melee decimates that base's S.H.I.E.L.D. forces, and the splinter Avengers barely escape with their lives...the ones who manage to escape, anyway. The team's wounded, with S.H.I.E.L.D. on their tails, a dozen supervillains on the loose, and no place to run. With nowhere else to turn, Cloak's team makes a deal with the nearest available devil, Wilson Fisk. In exchange for releasing him from prison, they need a base of operations and the resources to recouperate and take down the Act once and for all.

This latest raid on S.H.I.E.L.D. facilities has the government steaming. The casualties are fairly low, and they managed to recapture several of the villains and a couple of the splinter Avengers, but the collateral damage was deemed unacceptable. They decide on their own to settle this once and for all. Each one fitted with an inhibitor collar that can be activated by remote, and will detonate if removal is attempted, the new Thunderbolts squadron is unleashed, with orders to find and capture the Secret Avengers, by any means necessary. When Iron Man protests, he and his team are placed on lockdown.

And that brings us right up to the end of issue four or so. Excluding neutral parties like the X-Men and the Thing, we have four distinct factions: Captain America's Secret Avengers, fighting nobly against the Registration; Iron Man's enforcers, defending the Act for the good of the nation; Cloak's crusaders, teaming with a supervillain in order to take down the government; and Maria Hill's S.H.I.E.L.D. and Thunderbolts, who want their order on their terms. The logical continuation would see Iron Man and Captain America's teams uniting to corral their rogue factions, and the future of the Act could go either way, depending on how brave Marvel wants to be. Moral ambiguity abounds, and with the right treatment both of the moderate sides can look like they're doing everything for the right reasons, while the fanatics can act fanatical without going wildly out of character. There's no need to compromise Captain America and Iron Man for a story like this, no need to senselessly slaughter minor characters, and absolutely no need to clone Thor.

Doesn't that sound like a better comic? And I'd write it for free.

All throughout the lead-up and duration of this series, Marvel's higher-ups have said that they're not endorsing either side, that neither group is "right." Meanwhile, Tony Stark's behind-the-scenes manipulation of longtime friends and colleagues, the pro-Registration side's willingness to play Odin and dance with devils, and Captain America's mere presence on the anti-Registration side, have told a very different story, a tale of clearly-defined good and evil, and no amount of panels where Tony Stark wonders about his choices or where Cap looks like a fanatic, will change that.

Then, there's all the smaller problems. Why are all the intellectuals on the pro-Registration side? Why are Tony Stark, Peter Parker, and Reed Richards acting so wildly out of character? And the one that's bugged me ever since I read Illuminati: how the hell can you justify the Stamford incident?

The new New Warriors may be a relatively inexperienced team, they may be in it more for the fame and money than they should, but of the four members I see on that team, three of them (Namorita, Night Thrasher, and Speedball) have been with the team since its inception, and have battled cosmic-level threats to the world. They routinely battled with the Sphinx (who at one point gained the ability to warp reality, as I recall), former Galactus herald Terrax the Tamer, and other fairly major villains. They've earned the right to some respect. Nitro, on the other hand, is something of a D-list villain, a character I hadn't even heard of until I picked up the Essential Official Guide to the Marvel Universe, whose power is "exploding" and whose only claim to fame is being involved in the death of Captain Marvel. This isn't a Year-One Power Pack going up against Dr. Doom, this is a group of fairly experienced heroes going after a lame villain. How is it that they were so "out of their league"? How is it that they could be blamed for the incident, that they "should have known better," and called the Avengers or some such nonsense? Last I checked, there wasn't a superhero phone tree. Is Spider-Man supposed to stop and call up the X-Men when Juggernaut starts rampaging through Times Square? How exactly does the hierarchy proceed? If Galactus shows up, do you call the Fantastic Four or the Avengers? I mean, the Avengers have more firepower, but the FF's got the experience. The idea that the New Warriors should have stepped back and called for help, that they were out of their league fighting freakin' Nitro, is beyond absurd.

No, Civil War started on the wrong foot and simply hasn't recovered. Here's how it should have gone.

First off, the Illuminati was a dumb idea which should have never been. It's elitist, it's vaguely racist, and it's another one of those "a dark secret from the earliest days of [insert character]'s history comes to light" plots that has been used, reused, and overused since Identity Crisis (see also: Gwen Stacy, Barry Allen, Professor Xavier, Thomas Wayne, etc.). Besides that, a major crisis, almost infinite in its scope, results from the dissolution of the relationship between the universe's primary heroes...seems to me that it's been done before.

The difference, of course, is that DC exploited a relationship that already existed, they didn't do a "JLA: Trinity" one-shot to set it up first.

What we do instead is a one-shot or brief miniseries (no more than 3 issues) about the new wave of "superhuman chic" sweeping the nation. Shows like the New Warriors and X-Statix have become increasingly popular, and every network wants to cash in. Meanwhile, the Masochist Marauders (from Spectacular Spider-Man #21--teens who fake muggings in order to get beaten up by superheroes) are a Jackass-style Internet sensation, and copycats have sprung up all over the country. Deaths due to radiation poisoning and other attempts to re-enact superhero fights and origins have been steadily rising. Rising up the bestseller charts is "The Capedemic: How So-Called Superheroes Endanger us All," a book which proposes the idea that the number of averted disasters and saved lives simply doesn't make up for the danger inherent in superheroes' existence. Finally, premiering this season on Fox: "Big Shoulders," a reality show about a new team of teenage superheroes operating in Chicago, the 'Chicago 7.'

Next, one tragedy isn't going to set the wheels in motion. There ought to be a series of events, and the first involves the Hulk. Things can go down pretty much the way they happened in Illuminati--Hulk rampages through a small midwestern town, completely unstoppable for the several minutes before heroes and Hulkbuster Units can arrive to bring him down. Midwestern politicians come under pressure to stop the spread of metahuman-related violence. When it was primarily an issue for New York, it was a different story, but superhuman menaces have begun popping up with more frequency in California and in various states across the country. S.H.I.E.L.D. is pressured by Congress to do something about the Hulk, hoping to use that as a stop-gap procedure, taking attention away from the metahuman problem. They go to the Avengers, telling Iron Man "he was on your team, he's your responsibility." Tony brings together Captain America, Hank Pym, Wasp (the only original Avengers left), Doc Samson (who knows the Hulk best), and Reed Richards ('cause he's a smartie), along with a somewhat sedated Bruce Banner. Bruce understands the problem at hand and agrees that he's simply too dangerous to continue roaming around the country. Tony suggests placing him on an orbital platform--he has several satellites in various places around the solar system that could be easily and remotely modified. They settle on a research satellite orbiting Mars. Bruce will be provided with all the amenities of home, and the self-replicating nanotechnology will ensure that any damage done by the Hulk is strictly temporary. Meanwhile, a research team on Earth will step up their quest to cure his condition. They send Bruce up, but he never makes it to the satellite. It's not clear who or what caused the malfunction.

Barely a week goes by before the Abomination breaks out of prison and ends up in St. Louis. The first superheroes on the scene are the Chicago 7, three weeks into the new season. The event goes live, with producers hoping to turn it into a publicity stunt. It works: Abomination stomps the rookie heroes, and their inexperience only makes things worse. Hundreds die, the property damage is astronomical, and all in the fifteen minutes it took for a Quinjet and several S.H.I.E.L.D. hovercraft to arrive from the East Coast. Within days, a superhero registration bill is circulating around Congress.

Now, this is about where my two ideas for this story diverge. For this first one, I'll accept the basic premise that it's an ideological war between Captain America and Iron Man, except, you know, without the idiocy.

Captain America makes a public speech against the bill, and the act's supporters need a spokesperson from the costume crowd. They end up picking Iron Man, due to his prestige and sway with the superhero community. Tony is torn, and as much as he may agree with Captain America, he can't help but wonder if maybe the act would be a good thing. He reads through the text several times, he speaks with the drafters and S.H.I.E.L.D. executives about the logistics. Everything would remain more or less the same, really. The superheroes would register with S.H.I.E.L.D., who would provide them with training and license cards, similar to the Avengers Membership Cards. The registered heroes would have the option of becoming S.H.I.E.L.D. employees, which would allow them to do their usual superheroing and civilian living, as long as they took the occasional S.H.I.E.L.D. mission. For this, they would receive a stipend and benefits (health insurance and life insurance are a bitch for the capes-and-tights set). All this information would be kept absolutely secret, and only top S.H.I.E.L.D. brass would have access to it.

And those who refused to register? If apprehended, they would be offered the chance to register. If they continued to refuse, they may be charged a fine, and they might face some time in prison.

Tony turns to Peter Parker for moral guidance. Peter's feelings about S.H.I.E.L.D. are mixed, and he's never been on the best of terms with the general populace. He and Tony have a long conversation about the matter, with Peter mostly playing the anti-registration side. That is, until Tony wonders aloud how many innocent lives might be saved if young superhumans had the proper training. Peter thinks back, back, to how a little professional training might have allowed him to reach Gwen Stacy in time, or to catch her without killing her, how a that extra edge against Doctor Octopus might have let him save Captain Stacy, how if he had gone to S.H.I.E.L.D. instead of the TV station, he might have been around to stop that robber...

It becomes clear to Peter that superheroes have been given great power, and the registration act is merely asking them to accept the responsibilities that come with such power. He joins Tony in support of the Registration Act. Tony immediately sets out to get the best and brightest in the superhero community to figure out the logistics, to ensure that security, training, and enforcement all works out with the heroes' best interests in mind. Hank McCoy won't return his phone calls.

Meanwhile, the X-Men are placed in a difficult situation. Cyclops and Wolverine and their ilk see the Act for what it is: a broadened version of the Mutant Registration Acts that have circulated around Congress for years. Cyclops considers coming out in opposition, but fears that it may draw unnecessarily negative attention to the dwindling Mutant community. Supporting the Act, however, would be outright hypocrisy, and would go against everything Xavier ever stood for. Not wanting to make the school a fort against the United States government, he declares official neutrality on the subject. Wolverine is understandably upset by this and leaves the mansion in protest.

The Act passes, despite Captain America's public speeches in opposition. Things initially appear to be going well. The superhero-related shows that started much of this ruckus have been quietly cancelled, superheroes are registering voluntarily by the dozens, and the anti-registration heroes? Reed Richards registers, as do Sue and Ben, but Johnny Storm refuses and leaves the team. Sue is still unsure about the whole thing, and Ben just won't talk about it, but both recognize that their public identities and publicly-known headquarters make it difficult to make a stand against the Act. Reed just hopes to oversee the registration operations, to ensure that identities are actually kept secret from prying eyes, and that the superhero training goes well, that all this will ultimately help the superheroes' cause.

It starts with Night Thrasher (and why not? Rather than needlessly kill him off, let's give him a purpose), who is in the process of battling a minor supervillain (I dunno, someone like Nitro, I suppose), when a police officer tries to arrest him. NT tries to tell him that he doesn't have time for this, but the cop draws his gun and insists. Night Thrasher knocks him out, then does the same with Nitro, leaving the supervillain in handcuffs with a power inhibitor collar on. NT escapes, but now is wanted for assaulting a police officer in addition to refusal to register. The scene plays out across the country: Hercules has to shrug off bullets from both sides while he stops a Hydra terror plot in Times Square, Darkhawk finds himself on the wrong end of a SWAT team after stopping a school bus from going over a bridge in San Francisco, and finally, some trigger-happy security guard fires at Speedball during a bank robbery/hostage situation, and the ricochets from his kinetic field kill two innocent bystanders. The media picks up the story nationwide, using Speedball as the prime example of why heroes need to register, how dangerous the anti-registration heroes are, and why young people shouldn't be allowed to operate as superheroes. The atmosphere shifts; first police are recommended across the country to use riot teams to apprehend rogue superheroes, then S.H.I.E.L.D. teams are dispatched onto regular superhero patrols. Iron Man offers his services to help round up the unregistered heroes, in hopes that he can take control before they start using lethal force in these apprehensions. Things are clearly spiraling out of control.

Meanwhile, Captain America has become the hero of the anti-registration movement. He steps into this role naturally, finding them across the country and running a sort of underground railroad for anti-reg heroes. Things with Cap proceed pretty much the same as they have in the regular series, what with him assembling his Secret Avengers and continuing their superheroic duties in secret. The only difference is that some of the heroes, particularly some of the younger ones, are chafing under Cap's cautionary ways. They want to break out and really fight back, but Cap doesn't want to start an all-out war with the American government. These dissenting heroes--including Black Cat, Jack Power, Deathlok, and War Machine (assuming all of them are still alive)--begin sneaking out of the base and causing anti-government havoc. Cap tries to hold together his Secret Avengers, despite the growing schism, but more and more of his team are choosing proactive methods over reactive ones. Of course, those methods are being spun by the media and the government to increase the furor over the issue, and it's quickly nationwide martial law on unregistered superheroes.

Tony Stark decides that this needs to end quickly; he realizes that the situation has long been out of his control, and he assembles his team to set a trap for Cap's Secret Avengers, in hopes of stopping the madness before America becomes a superhuman police state. The battle goes poorly for both sides; two of the Young Avengers and Dazzler are captured, while Sue Storm defects to Cap's side.

Cap and Tony don't fight, not really. Tony explains his position, how he just wants to help, he wants to wrest control of the system back from the government, and he can't do it alone. Things are out of his hands, and the vaguely anarchist actions of the Secret Avengers are only making things worse. Cap tells Tony that he's not trying to take down the government, he's just trying to hold his team together, and it's breaking apart under the pressure. He's disappointed that Tony would stoop so low as to set a trap for them, and he doesn't want to fight, but he's not going to back down. The Registration Act is wrong, and if Tony can't see that with S.H.I.E.L.D. patrols hunting down superheroes in the streets, then there may be no hope at all. Cap tells Tony to call off his troops, that this can still end peacefully, but Iron Man morosely looks away and pulls his mask back down. "I'm sorry, Cap. I can't do that." He fires his repulsor-ray, but finds it deflected back at him by Captain America's mighty shield. Cap calls for a retreat, while Iron Man's enforcers press on. They teleport away, with help from the Invisible Woman, and return to their base.

Back in the hideout, licking their wounds, the Secret Avengers have a breakdown. Cloak is pissed, and he leads the proactive heroes out of the hideout. Captain America is watching his resistance fall apart, and he wonders how it got to this point. Maybe Tony's right, maybe it would be better if they sat down with the pro-Registration folks and hammered out a compromise. Around that time, a young and idealistic superhero by the name of Gravity awkwardly steps up to Captain America, clumsily salutes, and introduces himself, saying how much of a pleasure it is to meet him, and how it was his shining example, his steadfast adherence to the ideals that make this country so great, which inspired him to put on a mask and tights and fight the good fight. Captain America shakes the young man's hand, and is suddenly reassured that he's doing the right thing. He thanks the lad, and solicits volunteers to go after their black sheep.

The splinter Avengers, however, aren't doing so hot. Following a raging Cloak, they decide to raid the S.H.I.E.L.D. prison facility where their teammates are being held, in hopes of causing serious damage while they're at it. They successfully break into the prison, not realizing that both the captured heroes and various villains are temporarily being held in the facility. The ensuing melee decimates that base's S.H.I.E.L.D. forces, and the splinter Avengers barely escape with their lives...the ones who manage to escape, anyway. The team's wounded, with S.H.I.E.L.D. on their tails, a dozen supervillains on the loose, and no place to run. With nowhere else to turn, Cloak's team makes a deal with the nearest available devil, Wilson Fisk. In exchange for releasing him from prison, they need a base of operations and the resources to recouperate and take down the Act once and for all.

This latest raid on S.H.I.E.L.D. facilities has the government steaming. The casualties are fairly low, and they managed to recapture several of the villains and a couple of the splinter Avengers, but the collateral damage was deemed unacceptable. They decide on their own to settle this once and for all. Each one fitted with an inhibitor collar that can be activated by remote, and will detonate if removal is attempted, the new Thunderbolts squadron is unleashed, with orders to find and capture the Secret Avengers, by any means necessary. When Iron Man protests, he and his team are placed on lockdown.

And that brings us right up to the end of issue four or so. Excluding neutral parties like the X-Men and the Thing, we have four distinct factions: Captain America's Secret Avengers, fighting nobly against the Registration; Iron Man's enforcers, defending the Act for the good of the nation; Cloak's crusaders, teaming with a supervillain in order to take down the government; and Maria Hill's S.H.I.E.L.D. and Thunderbolts, who want their order on their terms. The logical continuation would see Iron Man and Captain America's teams uniting to corral their rogue factions, and the future of the Act could go either way, depending on how brave Marvel wants to be. Moral ambiguity abounds, and with the right treatment both of the moderate sides can look like they're doing everything for the right reasons, while the fanatics can act fanatical without going wildly out of character. There's no need to compromise Captain America and Iron Man for a story like this, no need to senselessly slaughter minor characters, and absolutely no need to clone Thor.

Doesn't that sound like a better comic? And I'd write it for free.

And everything in its place

The Civil War rant is taking longer than I thought. Hopefully this will tide you over.

I just read some of the latest Paty Cockrum post (the part which was quoted here, in which (among other things), she calls all of Grant Morrison's fans "mindslaves" and roundly condemns his work on New X-Men, based mainly on his treatment of Magneto. She accuses him of "[jumping] a hundred fifty years into the supposed future in a vain attempt to keep Marvel from using the X folk again in current continuity!!!" and that's the part of the post and subsequent discussion that I'm going to focus on.

Let me lay my cards on the table here: I liked Morrison's New X-Men run. I came into it late, picking up the first trade and then the subsequent two, before jumping into the run at "Riot at Xavier's" and following it to the end in floppies. Aside from the first 12 issues of Astonishing, this is the only time I've ever regularly bought a core X-Men book (I used to pick up the issues with cool covers as a kid, and I bought X-Force/Statix up until El Guapo joined, and lately I've been following X-Factor). The story had its ups and downs; I was none too fond of anything involving Fantomex, and the last story was simply confusing, but Planet X was excellent. The Magneto-as-Xorn reveal was very well-done and completely unexpected, and it's a shame that it was so quickly made as unimportant and confusing as the rest of X-Men history.

Anyway, in the comments section on Blog@Newsarama, David Horenstein says "Plus, he’s [Grant Morrison] always been good at putting toys back in their box so the next person can play with them (in his words). Any changes that remain, remain, because most fans, writers, artists, and Marvel itself liked it." That got me thinking. There are some writers who are simply terrible at "putting the toys back" in the right place. How does Morrison figure into that? How does his X-Men run, and subsequent runs, figure into that?

Well, to begin, when I thought "who's bad at putting the toys back," my immediate thought was Mark Waid. Let's take a look at his Fantastic Four run, shall we? He killed Dr. Doom, he effectively killed Galactus, he killed and resurrected the Thing, and he made the Fantastic Four reviled around the world. Removing the two main villains in their rogues gallery couldn't have made it easy for whomever picked up the title next. Thankfully, it was J. Michael Straczynski, who doesn't really pay attention to things like "continuity" or "the point of the characters," and just takes the story on a one-way trip to nuttyville.

Waid's Flash run was similar; he ramped up the Flash's powers, introduced the Speed Force, replaced the Rogues with Replicant, introduced both the Flash legacy and Cobalt Blue legacy, time-traveled and Hypertime-traveled, and killed Wally no less than twice. How could you follow such a run? Waid did everything.

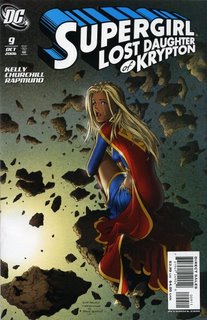

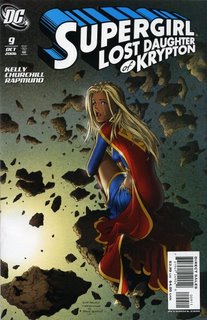

Jeph Loeb left Supergirl a blank slate, sure, but when he left Superman he still hadn't resolved the mystery of the faux Silver Age Krypton, and I think poor Clark Kent was still fired from the Daily Planet. Took the poor guy until OYL to recover from that blow to his supporting cast. Loeb left Hush with Batman's newest (and dumbest) villain still running around, both Catwoman and Riddler knowing Bruce's secret ID, Jason Todd resurrected--oh wait, not really, and a bunch of fans really puzzled as to what just happened.

So, what about Grant? He connected Animal Man to the universe's morphogenetic field, created a new Psycho Pirate, held a second Crisis, passed down the mantle of B'Wana Beast, tied Vixen into a greater dynasty, and gave Buddy the secrets of the universe (though made it vague as to whether or not he remembered them in the end). Finally, he restored some of the status quo (resurrecting Buddy's family) and left the book. With the JLA, he justified Green Arrow's trick arrows, revamped the Key, revitalized the JSA, revamped Queen Bee and the Shaggy Man/General Eiling/The General, made Plastic Man a formidable character, revamped Starro, introduced Zauriel, proved that the League can still function as a large team, introduced Prometheus, fought a giant war, finished Aztek's story arc, and pared the team down to a manageable level by the end. In New X-Men, he destroyed Genosha, made Magneto a martyr, developed a Mutant subculture, introduced the secondary mutations, introduced Cassandra Nova, killed Jean (again), hooked Scott up with Emma, fundamentally altered our perception of the Weapon X program, fleshed out the student population, introduced Xorn, revealed Xorn to be Magneto (albeit under the influence of Kick), did a fairly traditional Magneto-wants-to-kill-humans story, and left everything off with a futuristic tale (a staple of the X-books ever since "Days of Future Past") and a bittersweet ending for Scott.

So, how about the toys? The X-writers after Grant came back to the toybox to find some of their toys scuffed, some broken entirely, but a whole bunch of new toys and playsets to make up for it. Immediately, little Chucky and Chris started putting things back together and trying to set things up the way they were before, while Joss picked up Grant's favorite toys and ran with them. Sure, Grant made it relatively difficult to tell more Jean Grey stories, and he made Magneto back into a remorseless bastard and a world-class threat to humanity (though the personality changes could easily be explained away as influenced by the Kick), then promptly killed him (not usually a problem for Magneto). But look at what we got in return:

And so on. It's not that Grant left the toybox in a shambles, it's that Claremont and co. wanted to keep on playing the same game they've been playing since 1970-something, and Paty Cockrum is right there with 'em.

See, the job of a good writer isn't to leave the status quo undisturbed. It's to tell good stories. If you can tell a good story without altering the status quo, go for it. Plenty of folks have, and still do. But the X-Men's status quo had long been "confusion, retcon, resurrection, and inaccessibility," and what Morrison did was strip all that away, in order to tell very accessible (if 'Morrison-weird') X-Men stories, which paid attention to continuity without being bogged down in it, and which progressed the franchise so that other writers wouldn't get caught in the quagmire of inaccessible storylines, convoluted history, and boring, static characters, which has plagued the X-Men for at least the last decade and a half. Half of the reason for suckiness since then is the systematic dismantling of what he created, reducing things back to the old standard rather than moving the story forward. Only Joss Whedon ran with the ideas, creating new villains and bringing in new ideas, playing with the characters that dominated Grant's run, and trying to move X-Men singlehandedly out of stagnation, while Chris Claremont and the others just made the remnants of Grant's run as convoluted as any other piece of X-Men history, what with twin brothers and false revelations and whatnot. And then Decimation comes along and takes out the elements of subculture which Grant cultivated so well, leaving the X-Men in a weird sort of limbo.

There are three types of comic stories: Static, Progressive, and Regressive. Static stories exist wholly within a given status quo. Sometimes these are quite excellent (Alan Moore's in-continuity Superman stories come to mind), some are mere filler. Ultimately, these Static Stories make up the vast majority of comics, especially mid-Silver Age comics. Progressive stories advance the status quo somehow. These advancements may be minor (Perry and Alice White adopting Keith), or major (Hal Jordan going insane and being replaced with Kyle Rayner), and sometimes minor advancements occur within a generally static period. Regressive stories restore a previous status quo, and sometimes these are good (Green Lantern: Rebirth) while most of the time, they're terrible (JLA: Tenth Circle). While progress can be made for progress's sake, regression requires that special little dance to respect what you're retconning away while so as not to alienate the people who liked the changes, while also trying to make the old ways look new, interesting, and viable, since the changes were presumably made because the old ways lacked that.

The nice thing about progressive stories is that they almost universally open up new avenues for other writers to tell new and different stories. Alan Moore's changes to Swamp Thing transformed the character from a mediocre horror feature to the first of a pantheon of new gods for the DCU. Grant's changes to Animal Man paved the way for subsequent writers to tie him into the larger Elemental tapestry, to make him master of the Red, as Swamp Thing masters the Green. Mark Waid's Flash run altered the protagonist's powers and left him a married man, but all his forays into the timestream left a whole chunk of Wally's character unexplored and unexploited, and it's in that more down-to-earth realm that Geoff Johns's follow-up run excelled. Grant Morrison's New X-Men run is no different, and Joss Whedon's work proves it.

Can you imagine if Moore's Swamp Thing had been followed with a regressive writer? Can you imagine someone like Chris Claremont coming in and having Swamp Thing discover that the Green was all a hallucination, prompted by the Floronic Man, and that he really was Alec Holland after all? What great stories would we have lost? The Elementals are now fundamentally tied into the DC universe, much like the Endless and the Order/Chaos conflict. Imagine what would have been lost if someone had decided they liked the straight horror more. Imagine what would have been lost if someone came into Animal Man and bring Buddy back to his Silver Age-y roots, losing the philosophical trappings and the elemental-esque connection that Morrison had introduced. Would he be nearly as popular a character today? Would he have shown up in World War III and 52? Imagine if someone wrote a story which invalidated all of Morrison's contributions to the Doom Patrol, and turned the team back into lame X-Men wannabes...oh, wait. Sorry.

The point of all this rambling is that comic storytelling ought to be primarily progressive. If you can maintain momentum and suspense and interest with static storytelling (I'm looking at you, Paul Dini's Detective Comics), then by all means, do so. But most good stories come from moving things forward. Think of comics like a relay race; you run your part, but then pass the rod to the next person in the line, and they'll hand it off somewhere down the track. Even the best regressive stories still advance the situation somehow (going back to GL: Rebirth, in undoing Hal's death and the Parallax debacle, they redefined the core concepts of the Green Lanterns, introduced Parallax as a new villain, and changed the way the Corps operates). To continue the race metaphor, this is when the track has circled around back to the starting point; yet the runners have been moving forward the whole time. If you hand it to the next girl and immediately she starts running backward, then what you've done has been ultimately worthless.

So, Paty Cockrum, why don't you recognize comic characters for what they are. They aren't icons that can remain trapped in amber; even Mickey Mouse has had to roll with the changes. They're characters, and characters have to develop, change, and grow. Grant Morrison's New X-Men run was radical because it kicked the X-Men out of their fifteen-year slump, and all but begged for the next runner to end the cycle of "Magneto and Xavier's different viewpoints clash in a heated battle -> Status quo is restored -> Resurrect -> Retcon -> Repeat." Claremont and others ignored Morrison's advice, and X-Men remains in that slump, with the exception of Astonishing, which actually decided to play with Morrison's new status quo, and is consequently the best X-Men book around (though I hear Mike Carey's doing good things with his title now). Marvel's not recovering from Grant's "insanity and ineptitude," they're recovering from the short-sighted, self-serving retcons employed by writers who couldn't stand to see things move out of their decades-long rut. Claremont had found his comfortable ass-groove, and damned if he was going to give it up for something as inconsequential as "better stories."

Move forward. Go ahead and undo what you don't like, but do it in a progressive fashion. Clone Magneto, pull him back out of the timestream, don't say "oh it was never actually him." It doesn't do anyone any good to just start running the other way.

I just read some of the latest Paty Cockrum post (the part which was quoted here, in which (among other things), she calls all of Grant Morrison's fans "mindslaves" and roundly condemns his work on New X-Men, based mainly on his treatment of Magneto. She accuses him of "[jumping] a hundred fifty years into the supposed future in a vain attempt to keep Marvel from using the X folk again in current continuity!!!" and that's the part of the post and subsequent discussion that I'm going to focus on.

Let me lay my cards on the table here: I liked Morrison's New X-Men run. I came into it late, picking up the first trade and then the subsequent two, before jumping into the run at "Riot at Xavier's" and following it to the end in floppies. Aside from the first 12 issues of Astonishing, this is the only time I've ever regularly bought a core X-Men book (I used to pick up the issues with cool covers as a kid, and I bought X-Force/Statix up until El Guapo joined, and lately I've been following X-Factor). The story had its ups and downs; I was none too fond of anything involving Fantomex, and the last story was simply confusing, but Planet X was excellent. The Magneto-as-Xorn reveal was very well-done and completely unexpected, and it's a shame that it was so quickly made as unimportant and confusing as the rest of X-Men history.

Anyway, in the comments section on Blog@Newsarama, David Horenstein says "Plus, he’s [Grant Morrison] always been good at putting toys back in their box so the next person can play with them (in his words). Any changes that remain, remain, because most fans, writers, artists, and Marvel itself liked it." That got me thinking. There are some writers who are simply terrible at "putting the toys back" in the right place. How does Morrison figure into that? How does his X-Men run, and subsequent runs, figure into that?

Well, to begin, when I thought "who's bad at putting the toys back," my immediate thought was Mark Waid. Let's take a look at his Fantastic Four run, shall we? He killed Dr. Doom, he effectively killed Galactus, he killed and resurrected the Thing, and he made the Fantastic Four reviled around the world. Removing the two main villains in their rogues gallery couldn't have made it easy for whomever picked up the title next. Thankfully, it was J. Michael Straczynski, who doesn't really pay attention to things like "continuity" or "the point of the characters," and just takes the story on a one-way trip to nuttyville.

Waid's Flash run was similar; he ramped up the Flash's powers, introduced the Speed Force, replaced the Rogues with Replicant, introduced both the Flash legacy and Cobalt Blue legacy, time-traveled and Hypertime-traveled, and killed Wally no less than twice. How could you follow such a run? Waid did everything.

Jeph Loeb left Supergirl a blank slate, sure, but when he left Superman he still hadn't resolved the mystery of the faux Silver Age Krypton, and I think poor Clark Kent was still fired from the Daily Planet. Took the poor guy until OYL to recover from that blow to his supporting cast. Loeb left Hush with Batman's newest (and dumbest) villain still running around, both Catwoman and Riddler knowing Bruce's secret ID, Jason Todd resurrected--oh wait, not really, and a bunch of fans really puzzled as to what just happened.

So, what about Grant? He connected Animal Man to the universe's morphogenetic field, created a new Psycho Pirate, held a second Crisis, passed down the mantle of B'Wana Beast, tied Vixen into a greater dynasty, and gave Buddy the secrets of the universe (though made it vague as to whether or not he remembered them in the end). Finally, he restored some of the status quo (resurrecting Buddy's family) and left the book. With the JLA, he justified Green Arrow's trick arrows, revamped the Key, revitalized the JSA, revamped Queen Bee and the Shaggy Man/General Eiling/The General, made Plastic Man a formidable character, revamped Starro, introduced Zauriel, proved that the League can still function as a large team, introduced Prometheus, fought a giant war, finished Aztek's story arc, and pared the team down to a manageable level by the end. In New X-Men, he destroyed Genosha, made Magneto a martyr, developed a Mutant subculture, introduced the secondary mutations, introduced Cassandra Nova, killed Jean (again), hooked Scott up with Emma, fundamentally altered our perception of the Weapon X program, fleshed out the student population, introduced Xorn, revealed Xorn to be Magneto (albeit under the influence of Kick), did a fairly traditional Magneto-wants-to-kill-humans story, and left everything off with a futuristic tale (a staple of the X-books ever since "Days of Future Past") and a bittersweet ending for Scott.

So, how about the toys? The X-writers after Grant came back to the toybox to find some of their toys scuffed, some broken entirely, but a whole bunch of new toys and playsets to make up for it. Immediately, little Chucky and Chris started putting things back together and trying to set things up the way they were before, while Joss picked up Grant's favorite toys and ran with them. Sure, Grant made it relatively difficult to tell more Jean Grey stories, and he made Magneto back into a remorseless bastard and a world-class threat to humanity (though the personality changes could easily be explained away as influenced by the Kick), then promptly killed him (not usually a problem for Magneto). But look at what we got in return:

- New characters

- A new status quo for several members, most notably Scott and Emma

- A new way to look at the Mutant population and growing subculture

- A school which feels like a school, and not just a hangout for old superheroes

- The U-Men

- A new mechanism (secondary mutations) for updating old characters

- A new status quo for the Shi'ar

And so on. It's not that Grant left the toybox in a shambles, it's that Claremont and co. wanted to keep on playing the same game they've been playing since 1970-something, and Paty Cockrum is right there with 'em.

See, the job of a good writer isn't to leave the status quo undisturbed. It's to tell good stories. If you can tell a good story without altering the status quo, go for it. Plenty of folks have, and still do. But the X-Men's status quo had long been "confusion, retcon, resurrection, and inaccessibility," and what Morrison did was strip all that away, in order to tell very accessible (if 'Morrison-weird') X-Men stories, which paid attention to continuity without being bogged down in it, and which progressed the franchise so that other writers wouldn't get caught in the quagmire of inaccessible storylines, convoluted history, and boring, static characters, which has plagued the X-Men for at least the last decade and a half. Half of the reason for suckiness since then is the systematic dismantling of what he created, reducing things back to the old standard rather than moving the story forward. Only Joss Whedon ran with the ideas, creating new villains and bringing in new ideas, playing with the characters that dominated Grant's run, and trying to move X-Men singlehandedly out of stagnation, while Chris Claremont and the others just made the remnants of Grant's run as convoluted as any other piece of X-Men history, what with twin brothers and false revelations and whatnot. And then Decimation comes along and takes out the elements of subculture which Grant cultivated so well, leaving the X-Men in a weird sort of limbo.

There are three types of comic stories: Static, Progressive, and Regressive. Static stories exist wholly within a given status quo. Sometimes these are quite excellent (Alan Moore's in-continuity Superman stories come to mind), some are mere filler. Ultimately, these Static Stories make up the vast majority of comics, especially mid-Silver Age comics. Progressive stories advance the status quo somehow. These advancements may be minor (Perry and Alice White adopting Keith), or major (Hal Jordan going insane and being replaced with Kyle Rayner), and sometimes minor advancements occur within a generally static period. Regressive stories restore a previous status quo, and sometimes these are good (Green Lantern: Rebirth) while most of the time, they're terrible (JLA: Tenth Circle). While progress can be made for progress's sake, regression requires that special little dance to respect what you're retconning away while so as not to alienate the people who liked the changes, while also trying to make the old ways look new, interesting, and viable, since the changes were presumably made because the old ways lacked that.

The nice thing about progressive stories is that they almost universally open up new avenues for other writers to tell new and different stories. Alan Moore's changes to Swamp Thing transformed the character from a mediocre horror feature to the first of a pantheon of new gods for the DCU. Grant's changes to Animal Man paved the way for subsequent writers to tie him into the larger Elemental tapestry, to make him master of the Red, as Swamp Thing masters the Green. Mark Waid's Flash run altered the protagonist's powers and left him a married man, but all his forays into the timestream left a whole chunk of Wally's character unexplored and unexploited, and it's in that more down-to-earth realm that Geoff Johns's follow-up run excelled. Grant Morrison's New X-Men run is no different, and Joss Whedon's work proves it.

Can you imagine if Moore's Swamp Thing had been followed with a regressive writer? Can you imagine someone like Chris Claremont coming in and having Swamp Thing discover that the Green was all a hallucination, prompted by the Floronic Man, and that he really was Alec Holland after all? What great stories would we have lost? The Elementals are now fundamentally tied into the DC universe, much like the Endless and the Order/Chaos conflict. Imagine what would have been lost if someone had decided they liked the straight horror more. Imagine what would have been lost if someone came into Animal Man and bring Buddy back to his Silver Age-y roots, losing the philosophical trappings and the elemental-esque connection that Morrison had introduced. Would he be nearly as popular a character today? Would he have shown up in World War III and 52? Imagine if someone wrote a story which invalidated all of Morrison's contributions to the Doom Patrol, and turned the team back into lame X-Men wannabes...oh, wait. Sorry.

The point of all this rambling is that comic storytelling ought to be primarily progressive. If you can maintain momentum and suspense and interest with static storytelling (I'm looking at you, Paul Dini's Detective Comics), then by all means, do so. But most good stories come from moving things forward. Think of comics like a relay race; you run your part, but then pass the rod to the next person in the line, and they'll hand it off somewhere down the track. Even the best regressive stories still advance the situation somehow (going back to GL: Rebirth, in undoing Hal's death and the Parallax debacle, they redefined the core concepts of the Green Lanterns, introduced Parallax as a new villain, and changed the way the Corps operates). To continue the race metaphor, this is when the track has circled around back to the starting point; yet the runners have been moving forward the whole time. If you hand it to the next girl and immediately she starts running backward, then what you've done has been ultimately worthless.

So, Paty Cockrum, why don't you recognize comic characters for what they are. They aren't icons that can remain trapped in amber; even Mickey Mouse has had to roll with the changes. They're characters, and characters have to develop, change, and grow. Grant Morrison's New X-Men run was radical because it kicked the X-Men out of their fifteen-year slump, and all but begged for the next runner to end the cycle of "Magneto and Xavier's different viewpoints clash in a heated battle -> Status quo is restored -> Resurrect -> Retcon -> Repeat." Claremont and others ignored Morrison's advice, and X-Men remains in that slump, with the exception of Astonishing, which actually decided to play with Morrison's new status quo, and is consequently the best X-Men book around (though I hear Mike Carey's doing good things with his title now). Marvel's not recovering from Grant's "insanity and ineptitude," they're recovering from the short-sighted, self-serving retcons employed by writers who couldn't stand to see things move out of their decades-long rut. Claremont had found his comfortable ass-groove, and damned if he was going to give it up for something as inconsequential as "better stories."

Move forward. Go ahead and undo what you don't like, but do it in a progressive fashion. Clone Magneto, pull him back out of the timestream, don't say "oh it was never actually him." It doesn't do anyone any good to just start running the other way.

Saturday, September 23, 2006

This-ism, that-ism, -ism -ism -ism

I don't call myself a feminist. I've been rethinking this position lately, but I just can't seem to make myself take the plunge. I think women ought to be treated equally, and I think all of society benefits from equality, not just the minority. I've read Tekanji's How to be a Real Nice Guy, and while I have some contentions with the finer points of the "reverse -ism" argument, it's a nice combination of "things I ought to be more aware of" and "things that make me feel a little less guilty and worried." It underscores a lot of things (like privilege) that I've had a gut feeling about for years, and it's nice to see them put into words. It really helps me understand why I feel so torn over Politically Correct language (English major/editor anxieties about language vs. "liberal guilt" and respect for minorities). Despite all this, I have a hard time thinking of myself as a feminist. I tell people that I don't feel like I've earned the right, and every time I think about privilege, I feel even less certain of that.

Hm...it's at this point that I'm going to invoke the "Read More" link. Things get personal below the fold, folks. If you don't care, just come back tomorrow and enjoy a Civil War rant.

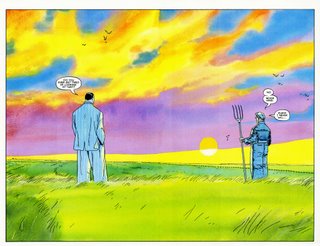

See, part of my problem is that I've always had an overactive sense of guilt. I've always tended toward being "the good kid," and I think a large part of that is due to a youth spent with an overactive imagination that would tend to pick out the worst possible consequences to any action, and frequently replay them. That, and I always identified with the good guys; I wanted to be Superman and He-Man and Optimus Prime (and yes, I credit cartoons and comic books with a significant part of building a strong moral fiber).

Though not humility, apparently. In case the general lack of personal info on my blog hasn't clued you in, I really don't like writing about myself. My feelings? Sure. My reactions to this week's Batman or whatever? You betcha. But who gives a damn about my past and my life? Whatever, I'm knee-deep in it now, might as well take the plunge.

So, due to a variety of little quirks in my upbringing, I'm always a little worried about being a racist, homophobic, bigoted jerk. I've said some horrendously homophobic things, and it was only around the end of my Junior year of High School that I got the bigot's epiphany. I've done whatever I could since then to promote equal rights and acceptance for the GLBTQ community--going to rallies, joining the Gay-Straight Alliance--mostly because I've felt so passionately about the subject, but also in hopes of atoning for the things I said in the past, so that I might clear my own conscience.

So I think that my personal history of prejudice has a major effect on my feelings about considering myself, with the privilege smorgasbord of being a young white middle-class heterosexual male, ideologically equal to someone who actually has to deal with discrimination and bigotry on a daily basis. The most I've done is attend a rally or two and watch The Vagina Monologues for V-Day. The last time I felt discrimination was when I was thirteen and old clerks followed me through the drugstore (well...unless you count religious discrimination, but even that's pretty minor). How does that measure up to people who have to fight every day to be recognized as people?

And then there's the little matter that I tend to play apologist/Devil's Advocate for some of the various majority groups to which I belong. As much as I can imagine myself into another person's shoes, the only perspective I can offer is that of a young white heterosexual middle-class male. It only reinforces the barriers between us to see that perspective dismissed or unconsidered, and sometimes I can't resist the impulse to say "well, look at it this way." It's only through understanding each other that we'll even be able to discourse equally, let alone treat each other equally. Good fences don't make good neighbors, they just make it harder to see the other side.

Yes, I believe women are people. I believe homosexuals ought to have the same rights as heterosexuals. I believe that everyone should be treated equally regardless of gender, skin color, religious affiliation, or sexual preference. I believe that comics aren't "meant for" any one audience, and that everyone should be able to pick up an issue of Justice League and find something that appeals to them. I believe that overt sexualization and stereotyping hurt comics' appeal far more than the occasional late book or fill-in artist. I want to see developed, defined, well-rounded characters of every sort, not characters who are defined by how developed and well-rounded their breasts are. I'd like to see equality, in comics and the real world, because I think equality ultimately benefits everyone. It's not a zero-sum game; you don't appeal to female readers at the expense of the male ones. You broaden the scope, you don't just shift the narrow focus. You open it up to everyone, and allow everyone to find something that includes them.

I believe that people ought to be treated with respect, whether they're real or four-color. I do what I can to treat real people with respect; I could do more, I'm sure, and I'll keep trying. I'd like to be in a position to treat four-color folks with respect, but that's really up to DC Comics, at this point (hint hint). I don't think that's enough for me to take up a label associated with people who have to fight to receive that sort of respect. Maybe I'm way off-base, here, and I wouldn't mind being told so. But it seems to me that calling myself a feminist would be the height of presumptuousness.

At this point, I'd usually go back and make sure this all makes sense, but I know that nothing I do to it will eliminate the rambling incoherence of it. This is going to be the Finnegan's Wake of comic blog posts. Sorry 'bout that, folks.

Hm...it's at this point that I'm going to invoke the "Read More" link. Things get personal below the fold, folks. If you don't care, just come back tomorrow and enjoy a Civil War rant.

See, part of my problem is that I've always had an overactive sense of guilt. I've always tended toward being "the good kid," and I think a large part of that is due to a youth spent with an overactive imagination that would tend to pick out the worst possible consequences to any action, and frequently replay them. That, and I always identified with the good guys; I wanted to be Superman and He-Man and Optimus Prime (and yes, I credit cartoons and comic books with a significant part of building a strong moral fiber).

Though not humility, apparently. In case the general lack of personal info on my blog hasn't clued you in, I really don't like writing about myself. My feelings? Sure. My reactions to this week's Batman or whatever? You betcha. But who gives a damn about my past and my life? Whatever, I'm knee-deep in it now, might as well take the plunge.

So, due to a variety of little quirks in my upbringing, I'm always a little worried about being a racist, homophobic, bigoted jerk. I've said some horrendously homophobic things, and it was only around the end of my Junior year of High School that I got the bigot's epiphany. I've done whatever I could since then to promote equal rights and acceptance for the GLBTQ community--going to rallies, joining the Gay-Straight Alliance--mostly because I've felt so passionately about the subject, but also in hopes of atoning for the things I said in the past, so that I might clear my own conscience.

So I think that my personal history of prejudice has a major effect on my feelings about considering myself, with the privilege smorgasbord of being a young white middle-class heterosexual male, ideologically equal to someone who actually has to deal with discrimination and bigotry on a daily basis. The most I've done is attend a rally or two and watch The Vagina Monologues for V-Day. The last time I felt discrimination was when I was thirteen and old clerks followed me through the drugstore (well...unless you count religious discrimination, but even that's pretty minor). How does that measure up to people who have to fight every day to be recognized as people?

And then there's the little matter that I tend to play apologist/Devil's Advocate for some of the various majority groups to which I belong. As much as I can imagine myself into another person's shoes, the only perspective I can offer is that of a young white heterosexual middle-class male. It only reinforces the barriers between us to see that perspective dismissed or unconsidered, and sometimes I can't resist the impulse to say "well, look at it this way." It's only through understanding each other that we'll even be able to discourse equally, let alone treat each other equally. Good fences don't make good neighbors, they just make it harder to see the other side.

Yes, I believe women are people. I believe homosexuals ought to have the same rights as heterosexuals. I believe that everyone should be treated equally regardless of gender, skin color, religious affiliation, or sexual preference. I believe that comics aren't "meant for" any one audience, and that everyone should be able to pick up an issue of Justice League and find something that appeals to them. I believe that overt sexualization and stereotyping hurt comics' appeal far more than the occasional late book or fill-in artist. I want to see developed, defined, well-rounded characters of every sort, not characters who are defined by how developed and well-rounded their breasts are. I'd like to see equality, in comics and the real world, because I think equality ultimately benefits everyone. It's not a zero-sum game; you don't appeal to female readers at the expense of the male ones. You broaden the scope, you don't just shift the narrow focus. You open it up to everyone, and allow everyone to find something that includes them.

I believe that people ought to be treated with respect, whether they're real or four-color. I do what I can to treat real people with respect; I could do more, I'm sure, and I'll keep trying. I'd like to be in a position to treat four-color folks with respect, but that's really up to DC Comics, at this point (hint hint). I don't think that's enough for me to take up a label associated with people who have to fight to receive that sort of respect. Maybe I'm way off-base, here, and I wouldn't mind being told so. But it seems to me that calling myself a feminist would be the height of presumptuousness.

At this point, I'd usually go back and make sure this all makes sense, but I know that nothing I do to it will eliminate the rambling incoherence of it. This is going to be the Finnegan's Wake of comic blog posts. Sorry 'bout that, folks.

Friday, September 22, 2006

Friday with Freakazoid!

After my "Le Mar" joke on Tuesday, I thought it'd be a good time for all of you to learn a little bit o' French.

Bon, merci! Au revoir!

Bon, merci! Au revoir!

Tuesday, September 19, 2006

Here there be solicits

Ahoy, ye landlubbers! Today, we'll be checkin' out the nastiest, deadliest crew o' black-hearted curs e'er t' sail these seven seas.

RAAAAWK! Solicitations!

Whazzat, Polly? Aye, aye, ye be a right fine bird, ye be. That's what I gets f'r list'nin' to Toungeless Pete. Like me parrot says, we'll be checkin' out the nastiest, deadliest crew o' black-hearted covers e'er to go on sale in a Winter that'll chill ye right to the bones. Yarrrrr.

First, on the starboard, we have the DSea books. P'raps there'll be a tale or two about the blue, briney deep, to read 'round the coals come nightfall, yarrrr.

Batman #660-661: Yarrr, John Ostrander be a fine writer, but that blackguard Mandrake makes me eye bleed, an' me empty socket glad it's empty. I'll be puttin' the black spot on this arc, mark me words.

Batman #660-661: Yarrr, John Ostrander be a fine writer, but that blackguard Mandrake makes me eye bleed, an' me empty socket glad it's empty. I'll be puttin' the black spot on this arc, mark me words.

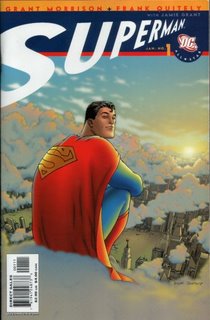

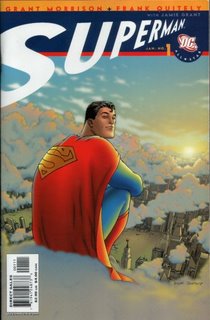

All-Star Superman #7: There be nothin to dislike about that Frank Quitely fella, an' that Grant Morrison be one crazy scallywag. I'll drop me doubloons f'r this'ne.

All-Star Superman #7: There be nothin to dislike about that Frank Quitely fella, an' that Grant Morrison be one crazy scallywag. I'll drop me doubloons f'r this'ne.

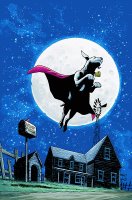

Superman #659: Yarr, a haunting image that be. Reminds me of me own fearless, faithful mutt, lost to me when I was but a pup m'self. A vitamin deficiency took 'im, it was, but 'e was the finest scurvy dog e'er to roll in th' filth on the beach.

Superman #659: Yarr, a haunting image that be. Reminds me of me own fearless, faithful mutt, lost to me when I was but a pup m'self. A vitamin deficiency took 'im, it was, but 'e was the finest scurvy dog e'er to roll in th' filth on the beach.

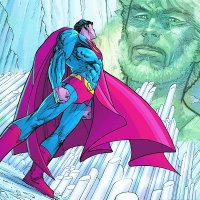

Action Comics #846: Mightn't this here be the new Zod? The beard's a fine choice, but th' John Waters moustache be makin' him look like a lily-livered dandy.

Action Comics #846: Mightn't this here be the new Zod? The beard's a fine choice, but th' John Waters moustache be makin' him look like a lily-livered dandy.

Supergirl & The Legion of Super-Heroes #25: Yarr, well that be spoilin' the surprise a bit, eh?

Supergirl & The Legion of Super-Heroes #25: Yarr, well that be spoilin' the surprise a bit, eh?

Avast! Off the port bow, that be the French clipper Le Marvel! Men, prepare for boardin'! We'll keelhaul the men and ravish the women!